For more information on the novel coronavirus and Covid-19, visit cdc.gov.

From the NBA to Vegas casinos, everyone’s clamoring for the $299 ring. But not even the company knows if it can actually detect Covid-19.

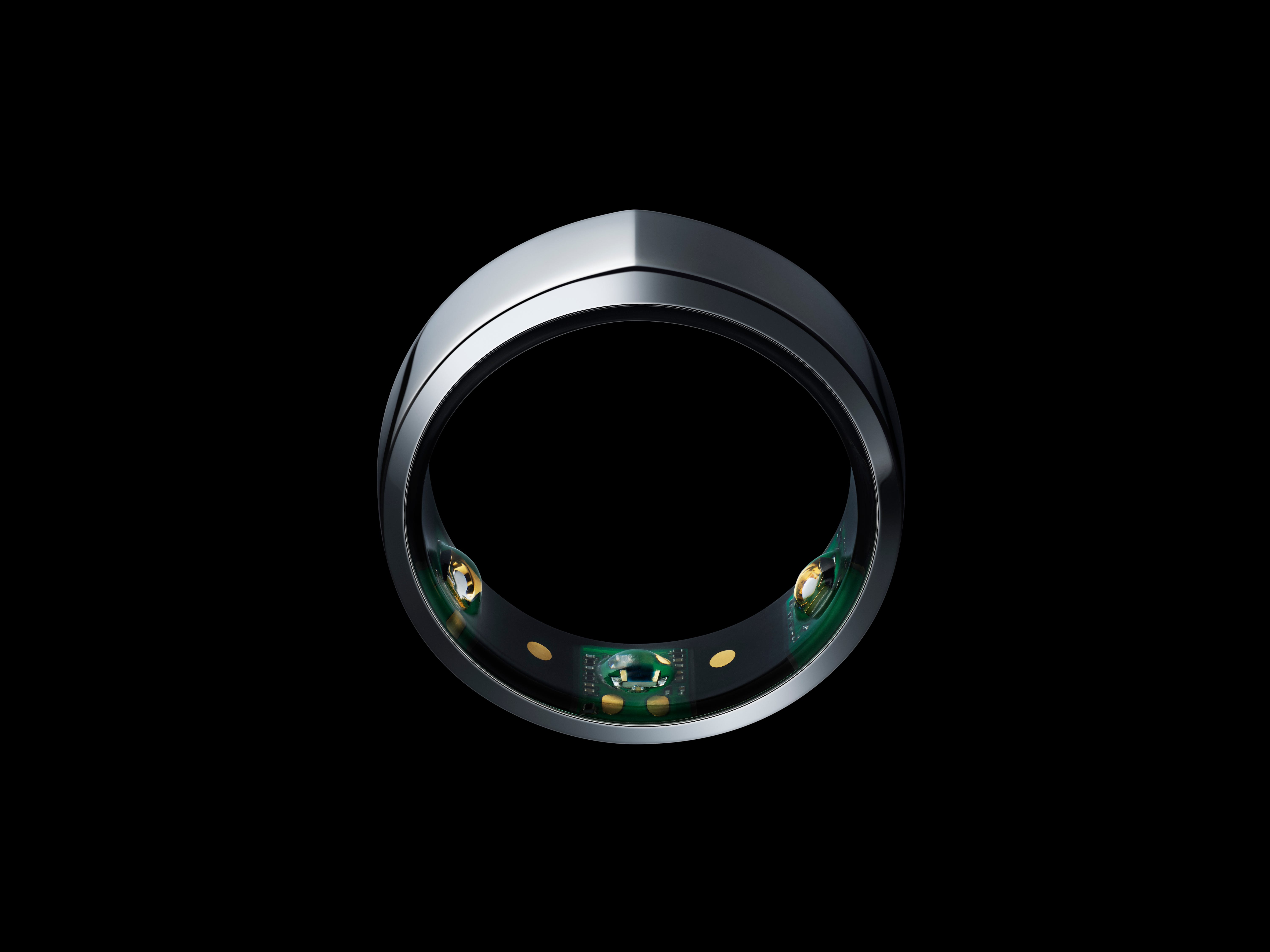

The Oura ring is suddenly everywhere. The $299 sleep tracking device has adorned the digits of Prince Harry, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, and, since July 9, 1,000 employees at the Venetian and Palazzo casinos in Las Vegas, and most of the NBA players entering the Walt Disney World “bubble” in Florida. The reason for the hype? The ring’s sensors monitor users’ health data, including heart rate, temperature, and respiratory rate. Oura crunches this data into a daily “readiness” score, which their connected app serves up to users each morning — the score indicates how hard to push yourself that day; for example, if you’ve slept badly, and your score is low, maybe skip the workout that day. Early studies also suggest the ring’s a useful early detection tool for signs of Covid-19.

With no vaccine in sight, wearable tech is having a field day in the time of Covid-19. PGA golfer Nick Watney credits his Whoop watch as the reason he got tested. Duke University launched CovIdentify, asking people with a Fitbit, Garmin watch, or iPhone to download their app in order to analyze if their data can predict infection or severity. Scripps Research Institute put out similar asks for their DETECT study, which aims to speed up identification of areas with outbreaks. And Fitbit, which Google intends to acquire, announced they’d built Ready for Work, a connected app that allows bosses to monitor their employees’ health. Some startups are even floating the idea of wearable smart patches.

It’s no wonder why employers are flocking to wearables like the Oura ring right now; doing something, anything that might potentially prevent or diagnose the disease is very alluring, especially for businesses that have been crushed by the contagion or by reopening restrictions. No one wearable has emerged as “the best” so far, and all studies, while encouraging, only have early-stage results, and aren’t peer reviewed. So how has a sleep-tracking gizmo that’s sold approximately 150,000 rings since early 2018, compared to Fitbit’s estimated 16 million in 2019 alone, become the post-Covid prerequisite?

From the beginning, Oura, which launched version one of their ring in 2015, billed itself as a health and lifestyle company, with a focus on sleep. “Sense. Understand. Inspire.” was splashed across its 2015 homepage. “We’ve always wanted to empower people to understand their full potential,” says Harpreet Singh Rai, Oura’s CEO, who joined Oura in 2017, after a decade managing investments at a global asset management firm. “We started with sleep because that’s an important area of health that’s underlooked. By understanding your own health, you can improve yourself.”

Oura, which is based in Oulu, Finland, and has operations in San Francisco and Helsinki, was founded in 2013 by a group of three friends who were searching for a wearable device to make their lives healthier. They believed that by tracking their data, they’d learn how lifestyle choices influenced their lives. Frustrated by the accuracy, style, and durability of current wrist wearables, they built their own — opting for a ring form factor, as their research showed that fingers were a good place to capture physiological data. In 2015, Oura raised a $2.3 million seed round and launched its first Oura ring to the public, a chunky, Goth-looking gizmo.

Doing something, anything that might potentially prevent or diagnose the disease is very alluring, especially for businesses that have been crushed by the contagion or by reopening restrictions.

In 2018, Oura upgraded the ring to a sleek titanium band that’s available in black, gray, and silver (plus a diamond-crusted $999 premium model). They added sensors, improved the fit, and added an inductive charging system. The ring, which resembles a utilitarian wedding band, weighs between four to six grams, depending on size, which for comparison, is on the lower end of engagement ring weight. Embedded in the band are the temperature and infrared LED sensors, plus a gyroscope and accelerometer, that track temperature, pulse rate, sleep data, and physical activity.

Prior to the pandemic, the ring was beloved by biohackers and techie types, but its price point kept it a niche product.

Enter Covid-19.

On March 5, Petri Hollmén, the 40-year-old founder of Lytti, a Finnish event management startup, flew from his home in Turku, Finland, to Zurich, Switzerland, then on to Tyrol, Austria, followed by an overnight stay at home, and then on to Stockholm, Sweden, for a day. Tyrol had become a coronavirus hotspot, so Hollmén self-quarantined, with his wife, three children, and dog, out of concern for his employees. He’d worn his Oura ring the entire time. On March 12, Oura gave him a readiness score of 54, around 30 points lower than normal. His Oura data indicated his temperature was elevated. He felt fine, but called his doctor anyways — he felt embarrassed about calling, he says. His doctor sent him for testing. He had the virus. Back to quarantining. His wife and eldest daughter also developed low-level symptoms, but his two other kids were unaffected. There wasn’t a lot of information about this in his community so he uploaded a selfie with his pup, Miisa, on Facebook, alongside a screed about his experience.

Hollmén’s post went viral, first in Finland and then worldwide. An Oura staffer noticed it, and slacked Rai the link. Hollmén’s elevated temperature didn’t surprise Rai. “Every year, around cold and flu season, users tell us that they saw [their] body temperature increasing,” he says. “This year, that data was obviously much more important.” Sensing a PR opportunity, Rai set up a call with Hollmén. “Thanks for posting that,” Rai told Hollmén. They discussed Hollmén’s recovery and his experience with Oura.

Then Rai paused. “Would you be willing to talk to journalists in the U.S.?”

Since early 2020, researchers across America had started pivoting their work to coronavirus-centric studies; detection, prognosis, treatments, cures. In early March, Ashley Mason, a psychiatric sleep researcher at UCSF, was informed that her investigation of saunas as a treatment for depression was on hold; all non-essential research had been nixed until further notice, they said. Her sauna study, which had not been funded by Oura, had used the company’s rings to track patients’ temperatures.

When she saw an article about Hollmén and his Oura ring potentially detecting coronavirus, she called Rai. “Have you seen the story?” she asked. She wondered: Could the rings possibly act as an early-detection tool for high-risk health care professionals? They were an especially vulnerable group — CDC data estimates that 98,000 American health care workers have been infected so far. Being able to identify infection early could help mitigate spread, and hopefully save lives. “I said, come on board,” Rai says. “We have to collect research to learn more about this illness.” Oura put up some funding for the study (after grants and other funds UCSF received, Oura contributed less than 15% of the funds).

The result: The UCSF TemPredict study, announced in April. Oura supplied rings to 2,000 frontline workers, and UCSF encouraged any Oura-owning member of the public to enroll in the study online as well. (They must complete a screening survey, answer daily surveys, and allow Oura to share their data.) The end goal, Rai says, is for UCSF to build an algorithm from the data that can identify onset, progression, and recovery patterns. He stressed that any supported studies are independently assessed, and that Oura does not influence the outcomes.

Other researchers with ongoing Oura partnerships also switched up their focus. In West Virginia, the Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute (RNI) developed AI models to forecast symptoms using physiological and behavioral biometrics from Oura data. On May 28, RNI reported that their A.I. platform detected symptoms three days before they materialized, with a 90% accuracy rate. They’ve scaled their program to health care employees at universities across America.

RNI’s preliminary findings caught the eye of the NBA Wearables Committee, who approve and validate players’ devices for use during gameplay. To keep their Disneyland social bubble well monitored, alongside regular Covid testing, they purchased 2,000 smart rings to monitor the players and staff (though wearing them is optional). Around the same time, Las Vegas Sands, which runs the Venetian and Palazzo casinos, also purchased 1,000 to pilot with their staff, and say they’ll purchase 9,300 more if the trial goes well. To aid companies in tracking possible infections in their workforce, Oura developed an enterprise management platform, which lets employers monitor ring-wearers’ health, and provides them with illness probabilities for every opted-in employee or NBA player.

The media hype around Oura — all savvily overseen by Rai — has been great for business. On March 17, Rai announced Oura had raised a $28 million Series B round. (To date, they’ve raised $75.5 million.) Since shelter-in-place took effect, numerous startups have folded, or furloughed to eke out their runway, but Oura’s team grew 20% between February and June, including new hires in social media and engineering. Just in the past month its social following grew by more than 100% on Twitter and Instagram, according to estimates from stat tracker Social Blade.

One of the company’s main challenges right now is keeping up with demand in the midst of supply chain issues created by coronavirus. The situation highlighted the inefficiencies of using Finland as the location for the company’s main fulfillment center. Shipping to the U.S. slowed, and many of the ring’s components that were sourced from China are taking longer to receive. And more and more research studies are asking to use Oura data. “We never imagined that in 2020 we’d be doing studies with nearly 50,000 enrollees,” says Rai. Oura can’t handle 50 new studies, he says, (their main focus is still consumer sleep tracking) so he has offered Oura’s open API share data with researchers. Despite building an app to let employers track employee biometrics, Rai is emphatic that the Oura ring “doesn’t diagnose or treat,” but says the data could be useful to people.

Meanwhile, researchers are going full speed ahead. In early March, Michael Snyder, PhD, a genetics professor at the Stanford School of Medicine, in conjunction with Fitbit turned his attention from researching wearables’ place in assessing risk for Lyme and Type 2 diabetes, to using wearables for Covid-19 detection. “We’re device agnostic,” Snyder says — any high-risk or exposed person who owns an Oura, Fitbit, Garmin, Samsung, or Apple watch can join his Covid-19 Wearables study, in which users link their wearable to an app and self-report additional symptoms. “We can detect Covid-19 with a smartwatch,” Snyder claims.

Whether or not the Oura ring is an effective Covid-19 alert system is still to be determined, and if research ends up discounting the device, that could become a major challenge for the company.

According to his preliminary data, algorithms detected elevated heart rates three of four days before symptoms appeared in around 80% of cases. “Heart rate is a better measure than skin temperature as a lot of people don’t get fever with Covid-19,” he says. However, so far, the data can’t differentiate between, say, Covid-19 and the common cold. And, at least according to Snyder, there’s no clear wearable winner. “We don’t know which wearable is best, as they all measure different things,” he says. “We’ll see which features turn out to be the most important.” Snyder believes that once the algorithms improve, most people will purchase wearables for early detection. “It’s a no-brainer,” he says.

Others wonder if Oura may be getting too much attention. “Without doubt Oura is the most successful smart ring company today,” says Mikko Nurmimaki, editor of Smart Ring News. “It is beautiful. But we are yet to see objective, medical evidence on the accuracy of detecting Covid-19.” Nurmimaki posits that Oura’s buzz has overshadowed smart rings like the CIRCUL, created by California startup Bodimetrics. Its SP02 sensors measure blood oxygen levels, which might be a better diagnostic.

Rishi Desai, the chief medical officer at Osmosis, a medical education platform, and former epidemic intelligence officer at the CDC, isn’t convinced. “Wearables aren’t a major part of the solution for the problem we have today,” he says. “Joe buying it today will not help Joe, today or tomorrow.” He does however see them as “increasingly important technology for problems that we have in the future” in that collected data from wearables will hopefully drive medical research that develops the cures of tomorrow. Desai, who objects to capturing temperature data from a finger because it’s not “a good measure of core temperature,” also says the high cost of Oura and most wearable tech makes it inaccessible to many, noting that “the people that are highest risk are living on the margins.”

Even so, William Haseltine, BA, PhD, an infectious disease expert at ACCESS Health International and author of A Family Guide to Covid suggests it’s a “good idea” for people to purchase wearables because they make people more aware of social distancing and their symptoms. “There is variable accuracy,” he admits, “but the ask is to call their doctor — that’s not an onerous intervention.” They give people back some autonomy, he says, “where they’ve been left to their own devices as the government isn’t protecting them.” And of course, he adds, their data’s valuable for epidemiologists.

Whether or not the Oura ring is an effective Covid-19 alert system is still to be determined, and if research ends up discounting the device, that could become a major challenge for the company. In the next few weeks, its data is likely going to be under more scrutiny; at Stanford, Snyder’s rolling out a text message system to alert users of wearables — including Oura rings and Fitbits — if their metrics suggest they have the virus.

Osmosis’ Desai is worried about this next step. “Can you imagine if everybody in New York City starts calling with a fast heart rate? It would completely overwhelm the system,” he says. The Oura might be the shiniest new tech toy right now, he says, but that shine could be a misdirection. “The most important wearable right now to be focusing on is masks,” he says. “Anything that’s not talking about masks as the wearable of choice is a distraction.”

"device" - Google News

July 20, 2020 at 12:32PM

https://ift.tt/39diOVG

How the Oura Ring Sleep Tracker Became the Hottest Device of the Pandemic | Marker - Marker

"device" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KSbrrl

https://ift.tt/2YsSbsy

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How the Oura Ring Sleep Tracker Became the Hottest Device of the Pandemic | Marker - Marker"

Post a Comment